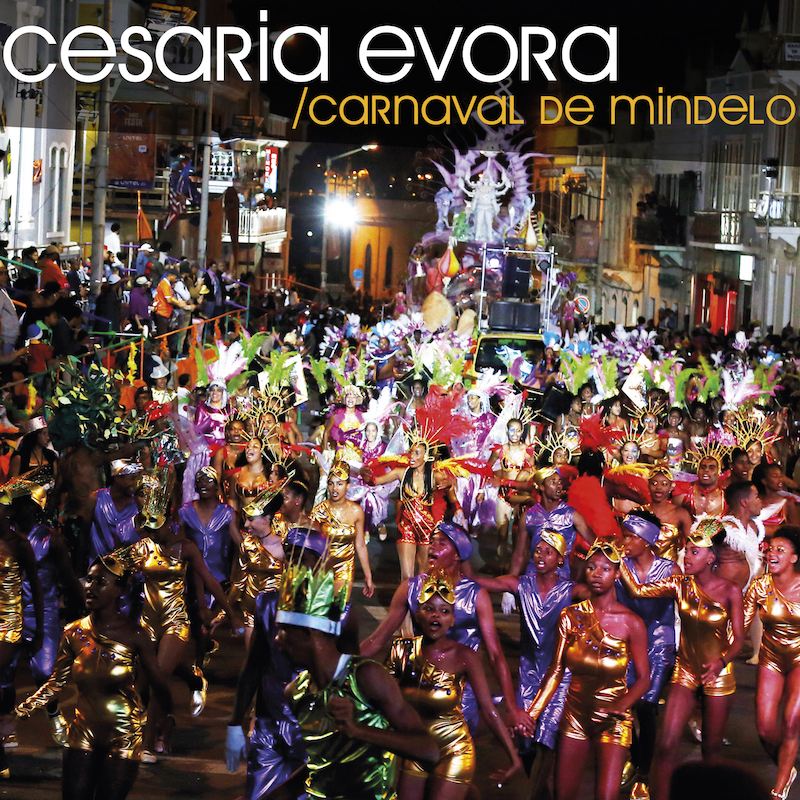

Cesaria Evora

Our Barefoot Diva

Site artiste : www.cesaria-evora.com

Facebook – Youtube – Twitter

Biography

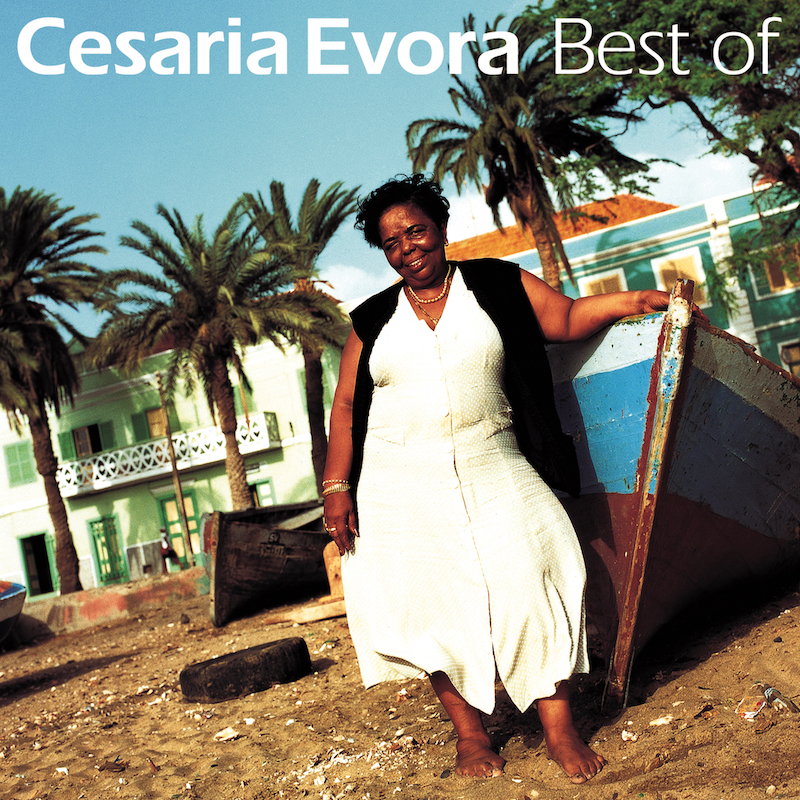

Cesaria Evora is first and foremost a mystery. She delights, fascinates and charms. Whatever our color, she is at once our friend, big sister and mother. When she comes to the Antilles, islands of zouk and beats, huge crowds stand in line at the ticket office. Everybody flocks to her concerts, from gros-ka fundamentalists to hardcore biguine-mazurka fans and addicts of rap and ragga: all want to immerse themselves in her melancholy. They take their shares of wrinkles and milk of youth. I have never had a chance to see her. The venues are always sold out. I can only imagine, gaze at her photos, be absorbed by her videos and dream of her tempi full of ancient pain.

In her book devoted to the Cabo-Verdean singer, Véronique Mortaigne makes it clear that a mystery such as hers cannot be solved, but only approached, experienced and revisited. This makes her fine writing and true sensitivity magnificent. She has understood that the secret of Cesaria Evora branches into many seams. Rather than a journey, she has to map erratic wanderings misted by fumes of punch and catchupa, through a geography of shadows, oases and light. Naturally, she has to listen to Cesaria – neither a peasant woman nor a ‘lady of the sea’, but a figure glimpsed in winding streets, bars and stores. She has to hear her delicious conversations with Vitoria, her good friend since childhood; learn the story of her fits of anger and torrent of insults; see her living in Mindelo, her island, town, port and hut, by a sea teeming with the hatreds and loves of those who were both forced to leave and compelled to remain. She sees the people who surround and love Cesaria, and those who support or take advantage of her. She sees her apron with its vast pockets, her plastic hair curlers and her waddling walk as she carries baskets of fish and herbs. She sees what Cesaria eats and learns the recipes, giving their number. She tastes the rum the singer shares freely, that did her so much harm and which the singer has no longer touched “since Christmas ’94”. She also has to understand the Cabo Verde archipelago and its initial catastrophe: Portuguese colonization and slavery. And then its struggle towards freedom and independence, its combats and alienations, its griefs and joys, and its mystery of life and salt in the growing threat of the Sahel.

Cesaria Evora is of that soil in the dryness of the sands. The book is not a biography, but an obscure revelation brimming with earth, life, music, simplicity, friendship, love, questions and lucidity. In its pages, I realize that Cesaria Evora is a Creole land in herself, whose diversity of imagination and people produces a music that connects with everyone, where melody, harmony and multiple rhythms encounter human suffering in a melting pot of blues, jazz and morna. I realize that Cesaria Evora is also a suffering – firstly hers, that of her life, her disastrous love affairs and a destructive intoxication to compensate for the wilting of the buds of hope. That familiar life of extremes ties in with ours in a tangible bond. When she sings, she brings us an entire life, escaping from the sordid bars and the fake gilt of socialite residences – the homes of Cabo Verde dotores who wanted to hear her sing. She also brings us her stationary exile, an irrepressible goal of exile that now lingers in each of us, drifting islands in a world that is a world unto itself. She reveals an incomparable sadness about everything possible. She tells us that happiness is lost but within reach. She speaks of black wounds of absence and silence. She describes the precious loam of memory. She tells of death and oblivion, loyalty and patience, liberty offered over bitter waves that one dares to tread. She tells of an open world of islands that are so accessible, so amenable to cultural fusions and the winds of the earth. She tells of inevitability, joy, hope, rounded strength and sharpened patience. Her feet are bare, her voice is naked, and so is her heart, proffered in a parure of all the graces. Among human beings, Cesaria is a queen.

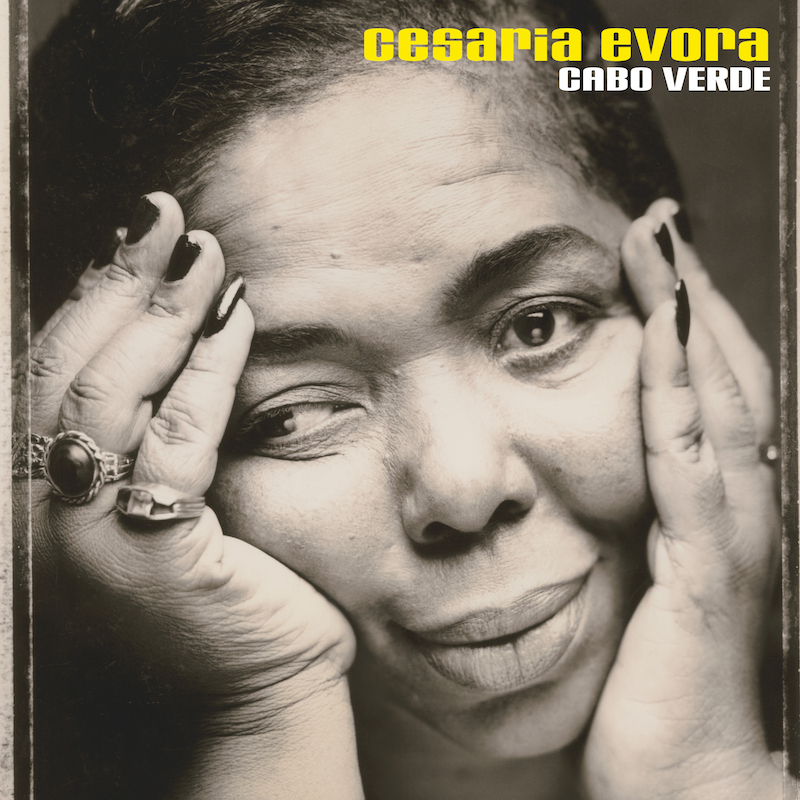

Article written by Patrick Chamoiseau, published in the newspaper Le Monde for the publication of the biography written by Véronique Mortaigne, shortly after the release of the album “Cabo Verde” in February 1997.

Patrick Chamoiseau, a French writer from Martinique, was born on December 3, 1953, in Fort-de-France. Author of novels, short stories and essays, he is a theoretician of Creole culture and also writes for the theater and cinema.

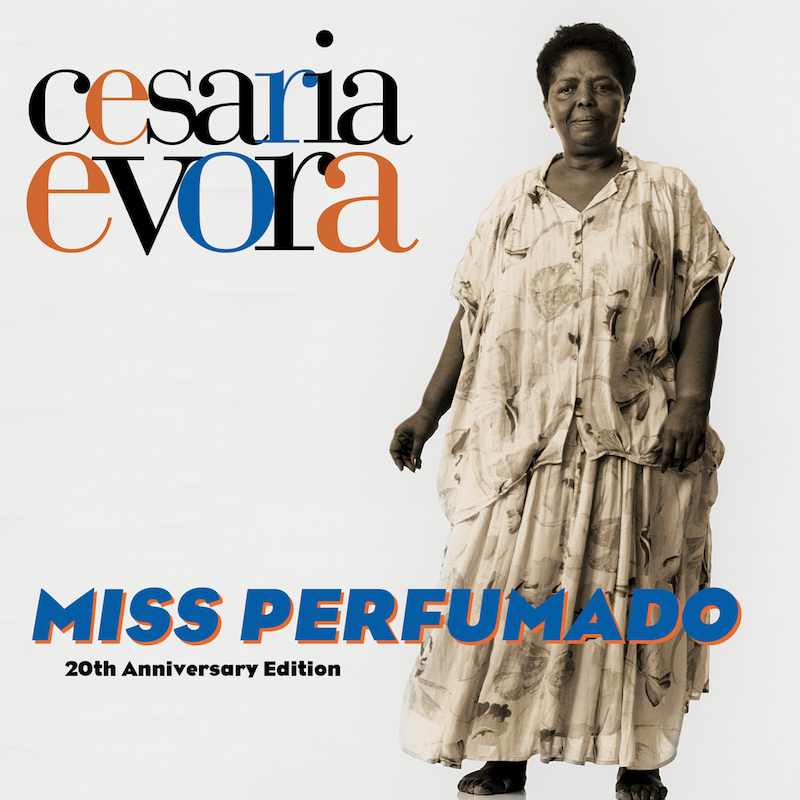

Albums

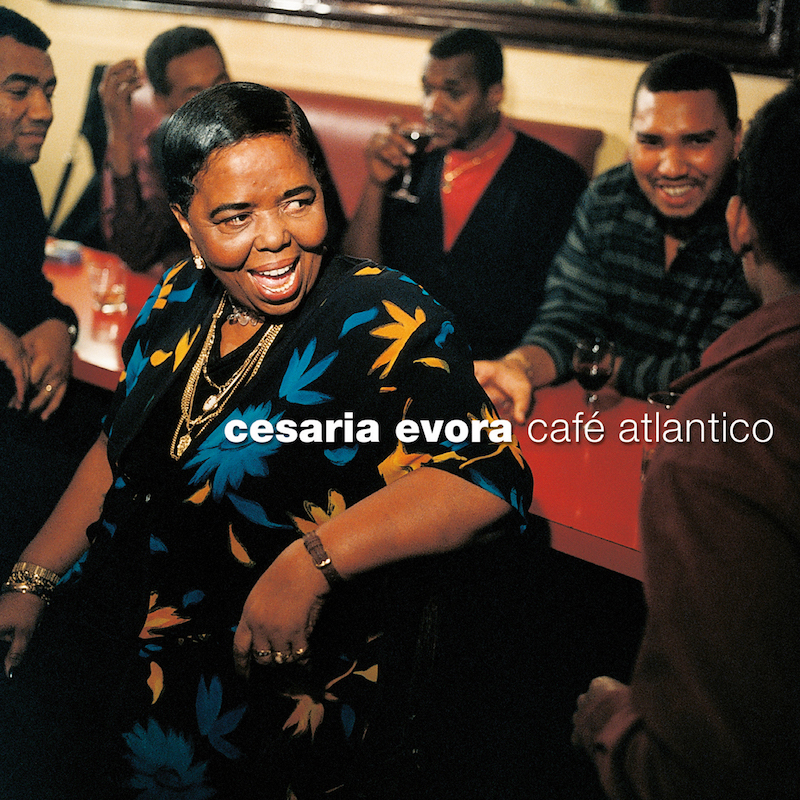

Café Atlantico – 1999

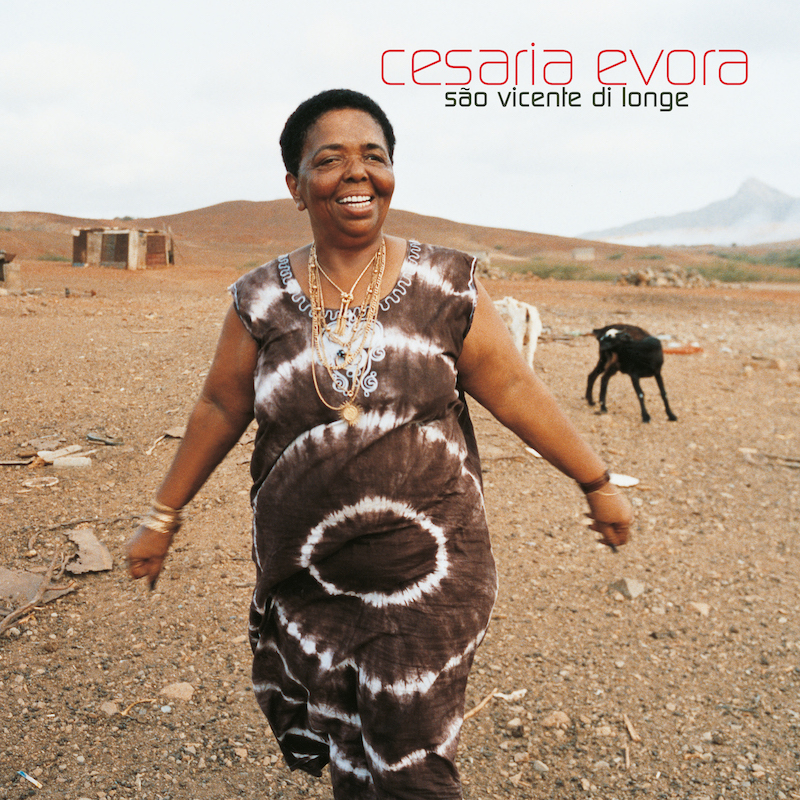

Sao Vicente di Longe – 2001

Mornas & Coladeras (Compilation) – 2002